Overview

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a condition that affects how a woman’s ovaries work.

The 3 main features of PCOS are:

- irregular periods – which means your ovaries do not regularly release eggs (ovulation)

- excess androgen – high levels of "male" hormones in your body, which may cause physical signs such as excess facial or body hair

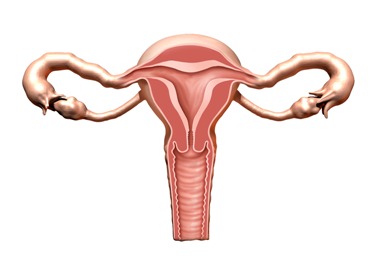

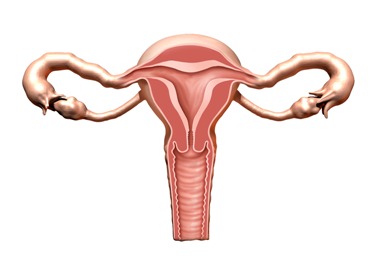

- polycystic ovaries – your ovaries become enlarged and contain many fluid-filled sacs (follicles) that surround the eggs (but despite the name, you do not actually have cysts if you have PCOS)

If you have at least 2 of these features, you may be diagnosed with PCOS.

Polycystic ovaries

Polycystic ovaries contain a large number of harmless follicles that are up to 8mm (approximately 0.3in) in size.

The follicles are underdeveloped sacs in which eggs develop. In PCOS, these sacs are often unable to release an egg, which means ovulation does not take place.

It's difficult to know exactly how many women have PCOS, but it's thought to be very common, affecting about 1 in every 5 women in the UK.

More than half of these women do not have any symptoms.

Signs and symptoms

If you have signs and symptoms of PCOS, they'll usually become apparent during your late teens or early 20s.

They can include:

PCOS is also associated with an increased risk of developing health problems in later life, such as type 2 diabetes and high cholesterol levels.

What causes PCOS?

The exact cause of PCOS is unknown, but it often runs in families.

The condition is associated with abnormal hormone levels in the body, including high levels of insulin.

Insulin is a hormone that controls sugar levels in the body.

Many women with PCOS are resistant to the action of insulin in their body and so produce higher levels of insulin to overcome this.

This contributes to the increased production and activity of hormones such as testosterone.

Being overweight increases the amount of insulin your body produces.

Treating PCOS

There's no cure for PCOS, but the symptoms can be treated. Speak to your GP if you think you may have the condition.

If you have PCOS and you're overweight, losing weight and eating a healthy, balanced diet can make some symptoms better.

Medications are also available to treat symptoms such as excessive hair growth, irregular periods and fertility problems.

If fertility medications are ineffective, a simple surgical procedure called laparoscopic ovarian drilling (LOD) may be recommended.

This involves using heat or a laser to destroy the tissue in the ovaries that's producing androgens, such as testosterone.

With treatment, most women with PCOS are able to get pregnant.

Symptoms

If you experience symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), they'll usually become apparent in your late teens or early 20s.

Not all women with PCOS have all of the symptoms. Each symptom can vary from mild to severe.

Some women only experience menstrual problems or are unable to conceive, or both..

Common symptoms of PCOS include:

- irregular periods or no periods at all

- difficulty getting pregnant (because of irregular ovulation or failure to ovulate)

- excessive hair growth (hirsutism) – usually on the face, chest, back or buttocks

- weight gain

- thinning hair and hair loss from the head

- oily skin or acne

You should talk to your GP if you have any of these symptoms and think you may have PCOS.

Fertility problems

PCOS is one of the most common causes of female infertility. Many women discover they have PCOS when they have difficulty getting pregnant

During each menstrual cycle, the ovaries release an egg (ovum) into the uterus (womb). This process is called ovulation and usually occurs once a month.

But, women with PCOS often fail to ovulate or ovulate infrequently, which means they have irregular or absent periods and find it difficult to get pregnant.

Risks in later life

Having PCOS can increase your chances of developing other health problems in later life. For example, women with PCOS are at increased risk of developing:

- type 2 diabetes – a lifelong condition that causes a person's blood sugar level to become too high

- depression and mood swings – because the symptoms of PCOS can affect your confidence and self-esteem

- high blood pressure and high cholesterol – which can lead to heart disease and stroke

- sleep apnoea – overweight women may also develop sleep apnoea, a condition that causes interrupted breathing during sleep

Women who have had absent or very irregular periods (fewer than three or four periods a year) for many years have a higher-than-average risk of developing cancer of the womb lining (endometrial cancer).

But, the chance of getting endometrial cancer is still small and can be minimised using treatments to regulate periods, such as the contraceptive pill or an intrauterine system (IUS).

Diagnosis

See your GP if you have any typical symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Your GP will ask about your symptoms to help rule out other possible causes and they'll check your blood pressure.

They'll also arrange for you to have a number of hormone tests to find out whether the excess hormone production is caused by PCOS or another hormone-related condition.

You may also need an ultrasound scan, which can show whether you have a high number of follicles in your ovaries (polycystic ovaries). The follicles are fluid-filled sacs in which eggs develop.

You may also need a blood test to measure your hormone levels and screen for diabetes or high cholesterol.

Diagnosis criteria

A diagnosis of PCOS can usually be made if other rare causes of the same symptoms have been ruled out and you meet at least two of the following three criteria:

- you have irregular periods or infrequent periods – this indicates that your ovaries don't regularly release eggs (ovulate)

- blood tests show you have high levels of "male hormones" such as testosterone (or sometimes just the signs of excess male hormones, even if the blood test is normal)

- scans show you have polycystic ovaries

As only two of these need to be present to diagnose PCOS, you won't necessarily need to have an ultrasound scan and blood test before the condition can be confirmed.

Referral to a specialist

If you are diagnosed with PCOS, you may be treated by your GP or referred to a specialist – either a gynaecologist (specialist in treating conditions of the female reproductive system) or an endocrinologist (specialist in treating hormone problems).

Your GP or specialist will discuss with you the best way to manage your symptoms. They will recommend lifestyle changes, and start you on any necessary medication.

Follow-up

Depending on factors like your age and weight, you may be offered annual checks of your blood pressure and screening for diabetes, if you're diagnosed with PCOS.

Treatment

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) can't be cured, but the symptoms can be managed.

Treatment options can vary because someone with PCOS may experience a range of symptoms, or just one.

The main treatment options are discussed in more detail below.

Lifestyle changes

In overweight women, the symptoms and overall risk of developing long-term health problems from PCOS can be greatly improved by losing excess weight.

Weight loss of just 5% can lead to a significant improvement in PCOS.

You can find out whether you're a healthy weight by calculating your body mass index (BMI), which is a measurement of your weight in relation to your height.

A normal BMI is 18.5-24.9. Use the BMI healthy weight calculator to work out whether your BMI is in the healthy range.

You can lose weight by exercising regularly and having a healthy, balanced diet.

Your diet should include plenty of fruit and vegetables, (at least five portions a day), whole foods (such as wholemeal bread, wholegrain cereals and brown rice), lean meats, fish and chicken.

Your GP may be able to refer you to a dietitian if you need specific dietary advice.

Medications

A number of medications are available to treat different symptoms associated with PCOS. These are described below.

Irregular or absent periods

The contraceptive pill may be recommended to induce regular periods, or periods may be induced by progesterone tablets (which can be given every 3-4 months, but can be given monthly).

This will also reduce the long-term risk of developing cancer of the womb lining (endometrial cancer) associated with not having regular periods.

An intrauterine (IUS) system) will also reduce this risk, but won't cause periods.

Fertility problems

A medication called clomifene is usually the first treatment recommended for women with PCOS who are trying to get pregnant.

Clomifene encourages the monthly release of an egg from the ovaries (ovulation).

If clomifene is unsuccessful in encouraging ovulation, another medication called metformin may be recommended.

Metformin is often used to treat type 2 diabetes, but it can also lower insulin and blood sugar levels in women with PCOS.

As well as stimulating ovulation, encouraging regular monthly periods and lowering the risk of miscarriage, metformin can also have other long-term health benefits, such as lowering high cholesterol levels and reducing the risk of heart disease.

Metformin is not licensed for treating PCOS in the UK, but because many women with PCOS have insulin resistance, it can be used "off-label" in certain circumstances to encourage fertility and control the symptoms of PCOS.

Possible side effects of metformin include nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, diarrhoea and loss of appetite.

As metformin can stimulate fertility, if you're considering using it for PCOS and not trying to get pregnant, make sure you use suitable contraception if you're sexually active.

The National Institute for Health and Care and Excellence (NICE) has more information about the use of metformin for treating PCOS in women who are not trying to get pregnant, including a summary of the possible benefits and harms.

Letrozole is sometimes used to stimulate ovulation instead of clomifene. This medication can also be used for treating breast cancer.

Use of letrozole for fertility treatment is "off-label". This means that the medication's manufacturer has not applied for a licence for it to be used to treat PCOS.

In other words, although letrozole is licensed for treating breast cancer, it does not have a license for treating PCOS.

Doctors sometimes use an unlicensed medication if they think it's likely to be effective and the benefits of treatment outweigh any associated risks.

If you're unable to get pregnant despite taking oral medications, a different type of medication called gonadotrophins may be recommended.

These are given by injection. There's a higher risk that they may overstimulate your ovaries and lead to multiple pregnancies.

Unwanted hair growth and hair loss

The combined oral contraceptive pill is usually used to treat excessive hair growth (hirsutism) and hair loss (alopecia).

A cream called eflornithine can also be used to slow down the growth of unwanted facial hair.

This cream does not remove hair or cure unwanted facial hair, so you may wish to use it alongside a hair removal product.

Improvement may be seen 4 to 8 weeks after treatment with this medicine.

Eflornithine cream is not always available on the NHS because some local NHS authorities have decided it's not effective enough to justify NHS prescription.

If you have unwanted hair growth, you may also want to remove the excess hair by using methods such as plucking, shaving, threading, creams or laser removal.

Laser removal of facial hair may be available on the NHS in some parts of the UK.

Sometimes medicines called anti-androgens may also be offered for excessive hair growth, which may include

- cyproterone acetate

- spironolactone

- flutamide

- finasteride

These medicines are not suitable if you are pregnant or trying to get pregnant.

For hair loss from the head, a minoxidil cream may be recommended for use on the scalp. Minoxidil is not suitable if you are pregnant or trying to get pregnant.

Other symptoms

Medications can also be used to treat some of the other problems associated with PCOS, including:

- weight-loss medication, such as orlistat, if you're overweight

- cholesterol-lowering medication (statins) if you have high levels of cholesterol in your blood

- acne treatments

IVF treatment

If you have PCOS and medicines do not help you to get pregnant, you may be offered in vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatment.

This involves eggs being collected from the ovaries and fertilised outside the womb. The fertilised egg or eggs are then placed back into the womb.

IVF treatment increased the chance of having twins or triplets if you have PCOS.

Surgery

A minor surgical procedure called laparoscopic ovarian drilling (LOD) may be a treatment option for fertility problems associated with PCOS that do not respond to medication.

Under general anaesthetic, your doctor will make a small cut in your lower tummy and pass a long, thin microscope called a laparoscope through into your abdomen.

The ovaries will then be surgically treated using heat or a laser to destroy the tissue that's producing androgens (male hormones).

LOD has been found to lower levels of testosterone and luteinising hormone (LH), and raise levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

This corrects your hormone imbalance and can restore the normal function of your ovaries.

Pregnancy risks

If you have PCOS, you have a higher risk of pregnancy complications, such as high blood pressure (hypertension), pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes and miscarriage.

These risks are particularly high if you're obese. If you're overweight or obese, you can lower your risk by losing weight before trying for a baby.