Overview

Alzheimer's disease is the most common type of dementia in the UK.

Dementia is the name for a group of symptoms associated with an ongoing decline of brain functioning. It can affect memory, thinking skills and other mental abilities.

The exact cause of Alzheimer's disease is not yet fully understood, although a number of things are thought to increase your risk of developing the condition.

These include:

- increasing age

- a family history of the condition

- untreated depression, although depression can also be one of the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease

- lifestyle factors and conditions associated with cardiovascular disease

Signs and symptoms of Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive condition, which means the symptoms develop gradually over many years and eventually become more severe. It affects multiple brain functions.

The first sign of Alzheimer's disease is usually minor memory problems.

For example, this could be forgetting about recent conversations or events, and forgetting the names of places and objects.

As the condition develops, memory problems become more severe and further symptoms can develop, such as:

- confusion, disorientation and getting lost in familiar places

- difficulty planning or making decisions

- problems with speech and language

- problems moving around without assistance or performing self-care tasks

- personality changes, such as becoming aggressive, demanding and suspicious of others

- hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that are not there) and delusions (believing things that are untrue)

- low mood or anxiety

Who is affected?

Alzheimer's disease is most common in people over the age of 65.

The risk of Alzheimer's disease and other types of dementia increases with age, affecting an estimated 1 in 14 people over the age of 65 and 1 in every 6 people over the age of 80.

But around 1 in every 20 cases of Alzheimer's disease affects people aged 40 to 65. This is called early- or young-onset Alzheimer's disease.

Getting a diagnosis

As the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease progress slowly, it can be difficult to recognise that there's a problem. Many people feel that memory problems are simply a part of getting older.

Also, the disease process itself may (but not always) prevent people recognising changes in their memory. But Alzheimer's disease is not a "normal" part of the ageing process.

An accurate and timely diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease can give you the best chance to prepare and plan for the future, as well as receive any treatment or support that may help.

If you're worried about your memory or think you may have dementia, it's a good idea to see your GP.

If possible, someone who knows you well should be with you as they can help describe any changes or problems they have noticed.

If you're worried about someone else, encourage them to make an appointment and perhaps suggest that you go along with them.

There's no single test that can be used to diagnose Alzheimer's disease. And it's important to remember that memory problems do not necessarily mean you have Alzheimer's disease.

Your GP will ask questions about any problems you're experiencing and may do some tests to rule out other conditions.

If Alzheimer's disease is suspected, you may be referred to a specialist service to:

- assess your symptoms in more detail

- organise further testing, such as brain scans if necessary

- create a treatment and care plan

How Alzheimer's disease is treated

There's currently no cure for Alzheimer's disease, but medicines are available that can help relieve some of the symptoms.

Various other types of support are also available to help people with Alzheimer's live as independently as possible, such as making changes to your home environment so it's easier to move around and remember daily tasks.

Psychological treatments such as cognitive stimulation therapy may also be offered to help support your memory, problem solving skills and language ability.

Outlook

People with Alzheimer's disease can live for several years after they start to develop symptoms. But this can vary considerably from person to person.

Alzheimer's disease is a life-limiting illness, although many people diagnosed with the condition will die from another cause.

As Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurological condition, it can cause problems with swallowing.

This can lead to aspiration (food being inhaled into the lungs), which can cause frequent chest infections.

It's also common for people with Alzheimer's disease to eventually have difficulty eating and have a reduced appetite.

There's increasing awareness that people with Alzheimer's disease need palliative care.

This includes support for families, as well as the person with Alzheimer's.

Can Alzheimer's disease be prevented?

As the exact cause of Alzheimer's disease is not clear, there's no known way to prevent the condition.

But there are things you can do that may reduce your risk or delay the onset of dementia, such as:

These measures have other health benefits, such as lowering your risk of cardiovascular disease and improving your overall mental health.

Dementia research

There are dozens of dementia research projects going on around the world, many of which are based in the UK.

If you have a diagnosis of dementia or are worried about memory problems, you can help scientists better understand the disease by taking part in research.

If you're a carer for someone with dementia, you can also take part in research.

You can sign up to take part in trials on the NHS Join Dementia Research website.

More information

Dementia can affect all aspects of a person's life, as well as their family's.

If you have been diagnosed with dementia, or you're caring for someone with the condition, remember that advice and support is available to help you live well.

Please visit our Dementia Guide for more information on Dementia.

Symptoms

The symptoms of Alzheimer's disease progress slowly over several years. Sometimes these symptoms are confused with other conditions and may initially be put down to old age.

The rate at which the symptoms progress is different for each individual.

In some cases, other conditions can be responsible for symptoms getting worse.

These conditions include:

- infections

- stroke

- delirium

As well as these conditions, other things, such as certain medicines, can also worsen the symptoms of dementia.

Anyone with Alzheimer's disease whose symptoms are rapidly getting worse should be seen by a doctor so these can be managed.

There may be reasons behind the worsening of symptoms that can be treated.

Stages of Alzheimer's disease

Generally, the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease are divided into 3 main stages.

Early symptoms

In the early stages, the main symptom of Alzheimer's disease is memory lapses.

For example, someone with early Alzheimer's disease may:

- forget about recent conversations or events

- misplace items

- forget the names of places and objects

- have trouble thinking of the right word

- ask questions repetitively

- show poor judgement or find it harder to make decisions

- become less flexible and more hesitant to try new things

There are often signs of mood changes, such as increasing anxiety or agitation, or periods of confusion.

Middle-stage symptoms

As Alzheimer's disease develops, memory problems will get worse.

Someone with the condition may find it increasingly difficult to remember the names of people they know and may struggle to recognise their family and friends.

Other symptoms may also develop, such as:

- increasing confusion and disorientation – for example, getting lost, or wandering and not knowing what time of day it is

- obsessive, repetitive or impulsive behaviour

- delusions (believing things that are untrue) or feeling paranoid and suspicious about carers or family members

- problems with speech or language (aphasia)

- disturbed sleep

- changes in mood, such as frequent mood swings, depression and feeling increasingly anxious, frustrated or agitated

- difficulty performing spatial tasks, such as judging distances

- seeing or hearing things that other people do not (hallucinations)

Some people also have some symptoms of vascular dementia

By this stage, someone with Alzheimer's disease usually needs support to help them with everyday living.

For example, they may need help eating, washing, getting dressed and using the toilet.

Later symptoms

In the later stages of Alzheimer's disease, the symptoms become increasingly severe and can be distressing for the person with the condition, as well as their carers, friends and family.

Hallucinations and delusions may come and go over the course of the illness, but can get worse as the condition progresses.

Sometimes people with Alzheimer's disease can be violent, demanding and suspicious of those around them.

A number of other symptoms may also develop as Alzheimer's disease progresses, such as:

- difficulty eating and swallowing (dysphagia)

- difficulty changing position or moving around without assistance

- weight loss – sometimes severe

- unintentional passing of urine (urinary incontinence) or stools (bowel incontinence)

- gradual loss of speech

- significant problems with short- and long-term memory

In the severe stages of Alzheimer's disease, people may need full-time care and assistance with eating, moving and personal care.

When to see a GP

If you're worried about your memory or think you may have dementia, it's a good idea to see a GP.

If you're worried about someone else's memory problems, encourage them to make an appointment and perhaps suggest that you go along with them.

Memory problems are not just caused by dementia – they can also be caused by depression, stress, medicines or other health problems.

Your GP can carry out some simple checks to try to find out what the cause may be, and they can refer you to a specialist for more tests if necessary.

Who can get it

Alzheimer's disease is thought to be caused by the abnormal build-up of proteins in and around brain cells.

One of the proteins involved is called amyloid, deposits of which form plaques around brain cells.

The other protein is called tau, deposits of which form tangles within brain cells.

Although it's not known exactly what causes this process to begin, scientists now know that it begins many years before symptoms appear.

As brain cells become affected, there's also a decrease in chemical messengers (called neurotransmitters) involved in sending messages, or signals, between brain cells.

Levels of one neurotransmitter, acetylcholine, are particularly low in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease.

Over time, different areas of the brain shrink. The first areas usually affected are responsible for memories.

In more unusual forms of Alzheimer's disease, different areas of the brain are affected.

The first symptoms may be problems with vision or language rather than memory.

Increased risk

Although it's still unknown what triggers Alzheimer's disease, several factors are known to increase your risk of developing the condition.

Age

Age is the single most significant factor. The likelihood of developing Alzheimer's disease doubles every 5 years after you reach 65.

But it's not just older people who are at risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. Around 1 in 20 people with the condition are under 65.

This is called early- or young-onset Alzheimer's disease and it can affect people from around the age of 40.

Family history

The genes you inherit from your parents can contribute to your risk of developing Alzheimer's disease, although the actual increase in risk is small.

But in a few families, Alzheimer's disease is caused by the inheritance of a single gene and the risks of the condition being passed on are much higher.

If several of your family members have developed dementia over the generations, and particularly at a young age, you may want to seek genetic counselling for information and advice about your chances of developing Alzheimer's disease when you're older.

The Alzheimer's Society website has more information about the genetics of dementia.

Down's syndrome

People with Down's syndrome are at a higher risk of developing Alzheimer's disease.

This is because the genetic fault that causes Down's syndrome can also cause amyloid plaques to build up in the brain over time, which can lead to Alzheimer's disease in some people.

The Down's Syndrome Association has more information about Down's syndrome and Alzheimer's disease on downs-syndrome.org.uk

Head injuries

People who have had a severe head injury may be at higher risk of developing Alzheimer's disease, but much research is still needed in this area.

Cardiovascular disease

Research shows that several lifestyle factors and conditions associated with cardiovascular disease can increase the risk of Alzheimer's disease.

These include:

You can help reduce your risk by:

Other risk factors

In addition, the latest research suggests that other factors are also important, although this does not mean these factors are directly responsible for causing dementia.

These include:

- hearing loss

- untreated depression (though depression can also be one of the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease)

- loneliness or social isolation

- a sedentary lifestyle

Diagnosis

It's best to see a GP if you're worried about your memory or are having problems with planning and organising.

If you're worried about someone else, encourage them to make an appointment and perhaps suggest going with them. It's often very helpful having a friend or family member there.

An accurate, timely diagnosis gives you the best chance to adjust, prepare and plan for the future, as well as access to treatments and support that may help.

Seeing a GP

Memory problems are not just caused by dementia – they can also be caused by:

- depression or anxiety

- stress

- medicines

- alcohol or drugs

- other health problems – such as hormonal disturbances or nutritional deficiencies

Read about common causes of memory loss.

A GP can carry out some simple checks to try to find out what the cause may be. They can then refer you to a specialist for assessment, if necessary.

A GP will ask about your concerns and what you or your family have noticed.

They'll also check other aspects of your health and carry out a physical examination.

They may also organise some blood tests and ask about any medicines you're taking to rule out other possible causes of your symptoms.

You'll usually be asked some questions and to carry out some memory, thinking, and pen and paper tasks to check how different areas of your brain are functioning.

This can help a GP decide if you need to be referred to a specialist for more assessments.

Referral to a specialist

If a GP is unsure about whether you have Alzheimer's disease, they may refer you to a specialist, such as:

- a psychiatrist (usually called an old age psychiatrist)

- an elderly care physician (sometimes called a geriatrician)

- a neurologist (an expert in treating conditions that affect the brain and nervous system)

The specialist may be based in a memory clinic alongside other professionals who are experts in diagnosing, caring for and advising people with dementia and their families.

There's no simple and reliable test for diagnosing Alzheimer's disease, but the staff at the memory clinic will listen to the concerns of both you and your family about your memory or thinking.

They'll assess your memory and other areas of mental ability and, if necessary, arrange more tests to rule out other conditions.

Mental ability tests

A specialist will usually assess your mental abilities, such as memory or thinking, using tests known as cognitive assessments.

Most cognitive assessments involve a series of pen and paper tests and questions, each of which carries a score.

These tests assess a number of different mental abilities, including:

- short- and long-term memory

- concentration and attention span

- language and communication skills

- awareness of time and place (orientation)

- abilities related to vision (visuospatial abilities)

It's important to remember that test scores may be influenced by a person's level of education.

For example, someone who cannot read or write very well may have a lower score, but they may not have Alzheimer's disease.

Similarly, someone with a higher level of education may achieve a higher score, but still have dementia.

These tests can therefore help doctors work out what's happening, but they should never be used by themselves to diagnose dementia.

Other tests

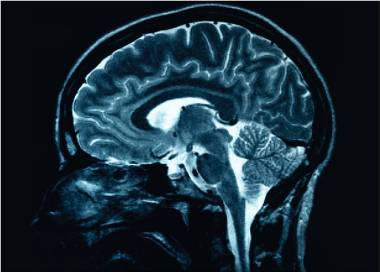

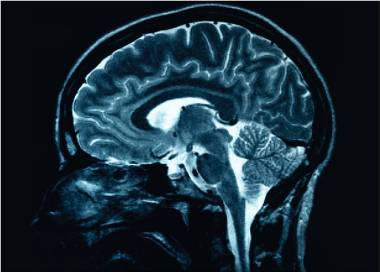

To rule out other possible causes of your symptoms and look for possible signs of damage caused by Alzheimer's disease, your specialist may recommend having a brain scan.

This could be a:

- CT scan – several X-rays of your brain are taken at slightly different angles and a computer puts the images together

- MRI scan – a strong magnetic field and radio waves are used to produce detailed images of your brain

After diagnosis

It may take several appointments and tests over many months before a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease can be confirmed, although often it may be diagnosed more quickly than this.

It takes time to adapt to a diagnosis of dementia, for both you and your family.

Some people find it helpful to seek information and plan for the future, but others may need a longer period to process the news.

It might help to talk things through with family and friends, and to seek support from the Alzheimer's Society.

As Alzheimer's disease is a progressive illness, the weeks to months after a diagnosis is often a good time to think about legal, financial and healthcare matters for the future.

Treatment

There's currently no cure for Alzheimer's disease. But there is medication available that can temporarily reduce the symptoms.

Support is also available to help someone with the condition, and their family, cope with everyday life.

Medicines

A number of medicines may be prescribed for Alzheimer's disease to help temporarily improve some symptoms.

The main medicines are:

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors

These medicines increase levels of acetylcholine, a substance in the brain that helps nerve cells communicate with each other.

They can currently only be prescribed by specialists, such as psychiatrists or neurologists.

They may be prescribed by a GP on the advice of a specialist, or by GPs that have particular expertise in their use.

Donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine can be prescribed for people with early- to mid-stage Alzheimer's disease.

The latest guidelines recommend that these medicines should be continued in the later, severe, stages of the disease.

There's no difference in how well each of the 3 different AChE inhibitors work, although some people respond better to certain types or have fewer side effects, which can include nausea, vomiting and loss of appetite.

The side effects usually get better after 2 weeks of taking the medication.

Memantine

This medicine is not an AChE inhibitor. It works by blocking the effects of an excessive amount of a chemical in the brain called glutamate.

Memantine is used for moderate or severe Alzheimer's disease. It's suitable for those who cannot take or are unable to tolerate AChE inhibitors.

It's also suitable for people with severe Alzheimer’s disease who are already taking an AChE inhibitor. Side effects can include headaches, dizziness and constipation but these are usually only temporary.

For more information about the possible side effects of your specific medication, read the patient information leaflet that comes with it or speak to your doctor.

Medicines to treat challenging behaviour

In the later stages of dementia, a significant number of people will develop what's known as behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD).

The symptoms of BPSD can include:

- increased agitation

- anxiety

- wandering

- aggression

- delusions and hallucinations

These changes in behaviour can be very distressing for both the person with Alzheimer's disease and their carer.

If coping strategies do not work, a consultant psychiatrist can prescribe risperidone or haloperidol, antipsychotic medicines, for those showing persistent aggression or extreme distress.

These are the only medicines licensed for people with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease where there's a risk of harm to themselves or others.

Risperidone should be used at the lowest dose and for the shortest time possible as it has serious side effects. Haloperidol should only be used if other treatments have not helped.

Antidepressants may sometimes be given if depression is suspected as an underlying cause of anxiety.

Sometimes other medications may be recommended to treat specific symptoms in BPSD, but these will be prescribed "off-label" (not specifically licensed for BPSD).

It's acceptable for a doctor to do this, but they must provide a reason for using these medications in these circumstances.

Treatments that involve therapies and activities

Medicines for Alzheimer's disease symptoms are only one part of the care for the person with dementia.

Other treatments, activities and support – for the carer, too – are just as important in helping people live well with dementia.

Cognitive stimulation therapy

Cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) involves taking part in group activities and exercises designed to improve memory and problem-solving skills.

Cognitive rehabilitation

This technique involves working with a trained professional, such as an occupational therapist, and a relative or friend to achieve a personal goal, such as learning to use a mobile phone or other everyday tasks.

Cognitive rehabilitation works by getting you to use the parts of your brain that are working to help the parts that are not.

Reminiscence and life story work

Reminiscence work involves talking about things and events from your past. It usually involves using props such as photos, favourite possessions or music.

Life story work involves a compilation of photos, notes and keepsakes from your childhood to the present day. It can be either a physical book or a digital version.

These approaches are sometimes combined. Evidence shows they can improve mood and wellbeing.

Prevention

As the exact cause of Alzheimer's disease is still unknown, there's no certain way to prevent the condition. But a healthy lifestyle can help reduce your risk.

Reducing your risk of cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease has been linked with an increased risk of Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia.

You may be able to reduce your risk of developing these conditions – as well as other serious problems, such as strokes and heart attacks – by taking steps to improve your cardiovascular health.

These include:

Other risk factors for dementia

The latest research suggests that other factors are also important, although this does not mean these factors are directly responsible for causing dementia.

These include:

- hearing loss

- untreated depression (although this can also be a symptom of dementia)

- loneliness or social isolation

- a sedentary lifestyle

The research concluded that by modifying all the risk factors we're able to change, our risk of dementia could be significantly reduced.

Staying mentally and socially active

There's some evidence to suggest that rates of dementia are lower in people who remain mentally and socially active throughout their lives.

It may be possible to reduce your risk of Alzheimer's disease and other types of dementia by:

- reading

- learning foreign languages

- playing musical instruments

- volunteering in your local community

- taking part in group sports, such as bowling

- trying new activities or hobbies

- maintaining an active social life

Interventions such as "brain training" computer games have been shown to improve cognition over a short period, but research has not yet demonstrated whether this can help prevent dementia.

In Wales

A free bilingual pack providing information for people in Wales that have been newly diagnosed with dementia is now available online.

The pack, entitled ‘Byw yn dda gyda dementia ar ôl diagnosis/Living well with dementia after diagnosis’, is easy to use and is broken down into sections that signpost people towards health and social care services, local services and other third sector agencies that offer support.

Individual information sheets from the pack can be downloaded for free from the Alzheimer’s Society website http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/livingwellwithdementia

The pack has been developed by Alzheimer's Society following the receipt of a grant from the Welsh Government. As part of the National Dementia Vision for Wales, the Welsh Government has committed to improving information on dementia by developing bilingual information packs for people diagnosed with dementia, their families, friends and carers; creating a dedicated dementia information helpline for Wales and extending the Welsh Government's Book Prescription Scheme to include dementia care.

Cheryl Williams, Dementia Information Liaison Officer for Alzheimer's Society, said:

‘A diagnosis of dementia may come as a shock and you may need some reassurance and support as there is much that can be done in the early stages that can help make life easier and more enjoyable. The pack is easy to use and is broken down into sections that signpost you towards health and social care services, local services and other third sector agencies that can support you.’

Please visit our Dementia Guide for more information on Dementia.

The information on this page has been adapted by NHS Wales from original content supplied by  NHS website nhs.uk

NHS website nhs.uk

Last Updated:

05/09/2024 14:08:55