Overview

A benign (non-cancerous) brain tumour is a mass of cells that grows relatively slowly in the brain.

Non-cancerous brain tumours tend to stay in one place and do not spread. It will not usually come back if all of the tumour can be safely removed during surgery.

If the tumour cannot be completely removed, there's a risk it could grow back. In this case it'll be closely monitored using scans or treated with radiotherapy.

Read about malignant brain tumour (brain cancer).

Types and grades of non-cancerous brain tumour

There are many different types of non-cancerous brain tumours, which are related to the types of brain cells affected.

Examples include:

- gliomas - tumours of the glial tissue, which hold and support nerve cells and fibres.

- meningiomas - tumours of the membranes that cover the brain

- acoustic neuromas - tumours of the acoustic nerve (also known as vestibular schwannomas)

- craniopharyngiomas - tumours near the base of the brain that are most often diagnosed in children, teenagers and young adults

- haemangioblastomas - tumours of the brain's blood vessels

- pituitary adenomas - tumours of the pituitary gland, a pea-sized gland on the under surface of the brain

The Cancer Research UK website has mroe information about the different types of brain tumours.

Brain tumours are graded from 1 to 4 according to how fast they grow and spread, and how likely they are to grow back after treatment.

Non-cancerous brain tumours are graded 1 to 2 because they tend to be slow growing and unlikely to spread.

They are not cancerous and can often be successfully treated, but they're still serious and can be life threatening.

Symptoms of non-cancerous brain tumours

The symptoms of a non-cancerous brain tumour depend on how big it is and where it is in the brain. Some slow-growing tumours may not cause any symptoms at first.

Common symptoms include:

- new, persistent headaches

- seizures (epileptic fits)

- feeling sick all the time, being sick, and drowsiness

- mental or behavioural changes, such as changes in personality

- weakness or paralysis, vision problems, or speech problems

When to see a GP

See a GP if you have symptoms of a brain tumour. While it's unlikely to be a brain tumour, these symptoms need to be assessed by a doctor.

The GP will examine you and ask about your symptoms. They may also test your nervous system.

If the GP thinks you may have a brain tumour or they're not sure what's causing your symptoms, they'll refer you to a brain and nerve specialist called a neurologist.

Causes of non-cancerous brain tumours

The cause of most non-cancerous brain tumours is unknown, but you're more likely to develop one if:

- you're over the age of 50

- you have a family history of brain tumours

- you have a genetic condition that increases your risk of developing a non-cancerous brain tumour - such as neurofibromatosis type 1, neurofibromatosis type 2, tuberous sclerosis, Turcot syndrome, Li-Fraumeni cancer syndrome, von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, and Gorlin syndrome

- you've had radiotherapy

Treating non-cancerous brain tumours

Treatment for a non-cancerous brain tumour depends on the type and location of the tumour.

Surgery is used to remove most non-cancerous brain tumours, and they do not usually come back after being removed. But sometimes tumours do grow back or become cancerous.

If all of the tumour cannot be removed, other treatments, such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy, may be needed to control the growth of the remaining abnormal cells.

Recovering from treatment for a non-cancerous brain tumour

After treatment, you may have persistent problems, such as seizures and difficulties with speech and walking. You may need supportive treatment to help you recover from, or adapt to, these problems.

Many people are eventually able to resume their normal activities, including work and sport, but it can take time.

You may find it useful to speak to a counsellor if you want to talk about the emotional aspects of your diagnosis and treatment.

The Brain Tumour Charity has links to support groups in the UK, and Brain Tumour Research also has details of helplines you can contact.

Symptoms

The symptoms of a benign (non-cancerous) brain tumour depend on its size and where it is in the brain.

Some slow-growing tumours may not cause any symptoms at first. When symptoms occur, it's because the tumour is putting pressure on the brain and preventing a specific area of the brain from working properly.

Increased pressure on the brain

Common symptoms of increased pressure within the skull include:

- new, persistent headaches – which are sometimes worse in the morning or when bending over or coughing

- feeling sick all the time

- drowsiness

- vision problems – such as blurred vision, double vision, loss of part of the visual field (hemianopia), and temporary vision loss

- epileptic fits (seizures) – which may affect the whole body or you may just have a twitch in one area

Location of the tumour

Different areas of the brain control different functions, so the symptoms of a brain tumour will depend on where it's located.

For example, a tumour affecting the:

- frontal lobe - may cause changes in personality, weakness in one side of the body and loss of smell

- temporal lobe - may cause memory loss (amnesia), language problems (aphasia) and seizures

- parietal lobe - may cause aphasia, numbness or weakness in one side of the body, and co-ordination problems (dyspraxia), such as difficulty dressing

- occipital lobe - may cause loss of vision on one side of the visual field (hemianopia)

- cerebellum - may cause balance problems (ataxia), flickering of the eyes (nystagmus) and vomiting

- brain stem - may cause unsteadiness and difficulty walking, facial weakness, double vision and difficulty speaking (dysarthria) and swallowing (dysphagia)

When to see a GP

It's important to see a GP if you have any symptoms.

While it's unlikely that you have a tumour, these type of symptoms need to be evaluated by a doctor so the cause can be identified.

If the GP is unable to find a more likely cause of your symptoms, they may refer you to a brain and nerve specialist called a neurologist for further assessment and tests, such as a brain scan.

Diagnosis

See a GP if you develop any of the symptoms of a benign (non-cancerous) brain tumour, such as a new, persistent headache.

They'll examine you and ask about your symptoms.

If they suspect you may have a tumour, or aren't sure what's causing your symptoms, they may refer you to a brain and nerve specialist (a neurologist) for further investigation.

Neurological examination

The GP or neurologist may test your nervous system to check for problems associated with a brain tumour.

This may involve testing your:

- arm and leg strength

- reflexes, such as your knee-jerk reflex

- hearing and vision

- skin sensitivity

- balance and co-ordination

- memory and mental agility using simple questions or arithmetic

Further tests

Other tests you may have to help diagnose a brain tumour include:

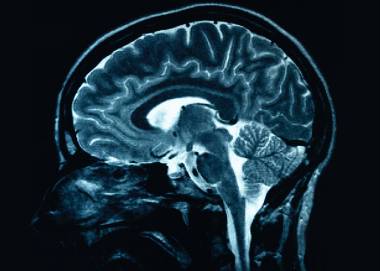

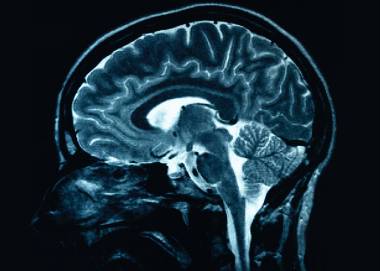

- a CT scan – where X-rays are used to build a detailed image of your brain

- an MRI scan – where a detailed image of your brain is produced using a strong magnetic field

- an electroencephalogram (EEG) – electrodes are attached to your scalp to record your brain activity and detect any abnormalities if it's suspected you're having epileptic fits

If a tumour is suspected, a biopsy may be carried out to establish the type of tumour and the most effective treatment.

Under anaesthetic, a small hole is made in the skull and a very fine needle is used to take a sample of tumour tissue.

You may need to stay in hospital for a few days after having a biopsy, although sometimes you may be able to go home on the same day.

Treatment

Benign (non-cancerous) brain tumours can usually be successfully removed with surgery and do not usually grow back.

It often depends on whether the surgeon is able to safely remove all of the tumour.

If there's some left, it can either be monitored with scans or treated with radiotherapy.

Rarely, some slow-growing non-cancerous tumours grow back after treatment and can change into malignant brain tumour (brain cancer) which are fast-growing and likely to spread.

You'll usually have follow-up appointments after finishing your treatment to monitor your condition and look for signs of the tumour recurring.

Your treatment plan

There are a number of different treatments for non-cancerous brain tumours.

Some people only need repeated scans to monitor the tumour and assess any growth. This is usually the case when a tumour is found by chance.

Some people will need surgery, particularly if they have severe or progressive symptoms, but sometimes non-surgical treatments are an option.

A group of different specialists will be involved in your care. They will recommend what they think is the best treatment option for you, but the final decision will be yours.

Before visiting hospital to discuss your treatment options, you may find it useful to write a list of questions you'd like to ask. For example, you may want to find out the advantages and disadvantages of particular treatments.

Surgery

Surgery is the main treatment for non-cancerous brain tumours. The aim is to remove as much of the tumour as safely as possible, without damaging the surrounding brain tissue.

In most cases, a procedure called a craniotomy will be performed. Most operations are carried out under a general anaesthetic which means you'll be asleep during the procedure.

But in some cases you may need to be awake and responsive, in which case a local anaesthetic will be used.

An area of your scalp will be shaved and a section of the skull cut out as a flap to reveal the brain and tumour underneath.

The surgeon will remove the tumour and fix the bone flap back into place with metal screws. The skin is closed with either sultures or staples.

If it is not possible to remove the entire tumour, you may need further treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

The Cancer Research UK website has more information about brain tumour surgery.

Radiosurgery

Some tumours are located deep inside the brain and are difficult to remove without damaging surrounding tissue. In these cases, a special type of radiotherapy called stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) may be used.

During radiosurgery, tiny beams of high-energy radiation are focused on the tumour to kill the abnormal cells.

Treatment consists of one session, recovery is quick, and you can usually go home on the same day.

Radiosurgery is only available in a few specialised centres in the UK. It's only suitable for some people, based on the characteristics, locations and size of their tumour.

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy

Conventional chemotherapy is occasionally used to shrink non-cancerous brain tumours or kill any cells left behind after surgery.

Radiotherapy involves using controlled doses of high-energy radiation, usually X-rays, to kill the tumour cells.

Chemotherapy is less frequently used to treat non-cancerous brain tumours. It's a powerful medication that kills tumour cells, and can be given as a tablet, injection or drip.

Side effects of these treatments can include tiredness, hair loss, nausea and reddening of your skin.

Read more about the side effects of radiotherapy and the side effects of chemotherapy.

Medicine to treat symptoms

You may also be given medication to help treat some of your symptoms before or after surgery, including:

- anticonvulsants to prevent epileptic fits (seziures)

- steroids to reduce swelling around the tumour, which can relieve some of your symptoms and make surgery easier

- painkillers to treat headaches

- anti-emetics to prevent vomiting

Recovery

After being treated for a benign (non-cancerous) brain tumour, you may need additional care to monitor and treat any further problems.

Follow-up appointments

Non-cancerous brain tumours can sometimes grow back after treatment, so you'll have regular follow-up appointments to check for signs of this.

Your appointments may include a discussion of any new symptoms you experience, a physical examination, and, occasionally, a brain scan.

It's likely you'll have follow-up appointments at least every few months to start with, but they'll probably be needed less frequently if no problems develop.

Side effects of treatment

Some people who have had a brain tumour can develop side effects of treatment months or years later, such as:

- cataracts

- problems with thinking, memory, language or judgement

- epilepsy

- hearing loss

- infertility

- migraine attacks

- a tumour developing somewhere else

- numbness, pain, weakness or loss of vision resulting from nerve damage (but these complications are rare)

- a stroke (this is rare)

If you or someone you care for has any worrying symptoms that develop after brain tumour treatment, see your doctor.

If you think it's a stroke, dial 999 immediately and ask for an ambulance.

Supportive treatment

Problems caused by a brain tumour do not always resolve as soon as the tumour is removed or treated.

For example, some people have persistent weakness, epileptic fits (seizures), difficulty walking and speech problems.

Extra support may be needed to help you overcome or adapt to any problems you have.

This may include therapies such as:

- physiotherapy to help with any movement problems you have

- occupational therapy to identify any problems you're having with daily activities, and arrange for any equipment or alterations to your home that may help

- speech and language therapy to help you with communication or swallowing problems

Some people may also need to continue taking medicine for seizures for a few months or more after their tumour has been treated or removed.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has made recommendations about the standards of care people with brain tumours should receive.

See the NICE guidance about improving outcomes for people with brain and other central nervous system tumours.

Driving and travelling

You may not be allowed to drive for a while after being diagnosed with a brain tumour.

How long you'll be unable to drive will depend on factors such as:

- whether you have had epileptic fits (seizures)

- the type of brain tumour you have

- where it is in your brain

- what symptoms you have

- what type of surgery you have had

If you're unsure whether or not you should be driving, do not drive until you have had clarification from the DVLA, your GP or specialist.

Driving against medical advice is both dangerous and against the law.

If you need to give up your driving licence, the DVLA will speak to your GP or specialist to determine when you can drive again.

With up-to-date scans and advice from your medical team, you may be allowed to drive after an agreed period.

This is usually after you have successfully completed medical tests to determine your ability to control a vehicle, and when the risk of having seizures is low.

The Cancer Research UK website has more information about brain tumours and driving.

Flying is usually possible when you have recovered from surgery, but you should let your travel insurance company know about your condition.

Lifestyle advice

If you have had radiotherapy, it's important to follow a healthy lifestyle to lower your risk of stroke.

This means stopping smoking if you smoke, eating a balanced diet and doing regular exercise.

However, there are limits to the exercise you should do.

Sports and activities

After being treated for a brain tumour, you might be advised to permanently avoid contact sports, such as rugby and boxing.

You can start other activities again, with the agreement of your doctor, once you have recovered.

Swimming unsupervised is not recommended for about a year after treatment because there's a risk you could have a seizure while in the water.

Sex and pregnancy

It's safe to have sex after treatment for a non-cancerous brain tumour.

Women may be advised to avoid becoming pregnant for 6 months or more after treatment.

If you're planning to become pregnant, you should discuss this with your medical team.

Going back to work

Tiredness is a common symptom after receiving treatment for a brain tumour. This often restricts your ability to return to work.

Although you may want to return to work and normal life as soon as possible, it's probably a good idea to work part time to begin with and only go back full time when you feel ready.

If you have had seizures, you should not work with machinery or at heights.

Help and support

A brain tumour is often life changing. You may feel angry, frightened and emotionally drained.

Your doctor or specialist may be able to refer you to a social worker or counsellor for help with the practical and emotional aspects of your diagnosis.

There are also a number of organisations that can provide help and support, such as The Brain Tumour Charity and Brain Tumour Research.

The information on this page has been adapted by NHS Wales from original content supplied by  NHS website nhs.uk

NHS website nhs.uk

Last Updated:

11/09/2024 14:31:22